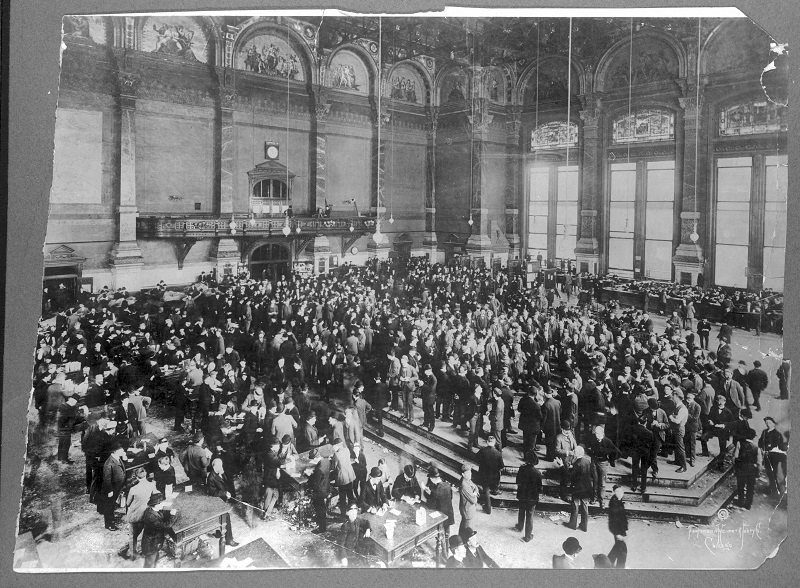

The Panic of 1893 was a true and severe financial panic lasting from May of 1893 to November, 1893, with a run on currency, and banks closing, and businesses and manufacturers not being able to open because they had not cash to pay workers or buy materials. The panic included precipitous declines in the stock market, the failure of Wall Street brokerage houses, and the failure of 158 national banks in 1893, mostly in the South and West. Other bank failures included 172 state banks, and 177 private banks, as well as 47 savings banks and 13 loan and trust companies and 16 mortgage companies. The panic started in New York and spread to the rest of the country. This was the atmosphere in which Florence Kelley and her colleagues began their work chronicling the economic conditions in the tenements and slums of Chicago.

For the first time in July of 1893 Chicago banks approved the issuance of clearinghouse loan certificates, foreshadowing the eventual suspension of cash payments. The Panic of 1893 was followed by an economic depression in employment and prices which lasted until 1897. Had the United States Federal Reserve Bank system existed, the panic probably would have been averted.

During the summer of 1893 commercial, industrial and manufacturing depression accompanied financial panic. Businesses failed and several major railroads, with Chicago as their transportation hub, went into receivership, and control of ‘unprecedented mileage’ was handed over to the state and federal courts in bankruptcy. For the year ending in June, 1894 over 125 railroads went into receivership. In the summer of 1893, when Florence Kelley was actively recording the conditions of unemployment and economic privation for the Illinois legislature, the political debate centered on the ‘silver question.’

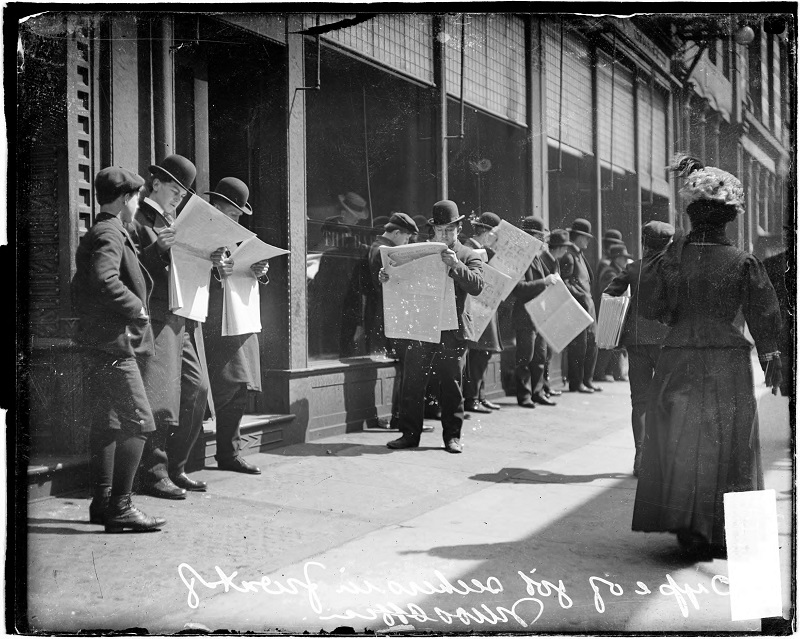

The year also saw prosecutions under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, aimed at curbing the abuses of monopolies, described in the powerful journalistic accounts of Henry Demarest Lloyd and others. By July and August of 1893 unemployment in factories was severe, and wage reductions widespread. Many banks were reporting declines in their gold reserves; the United States debt increased and money and gold flowed out of the country. The depression reached its low point in July of 1894, when Florence Kelley and her colleagues were busy enforcing the Factory and Workshop Inspection Statute.

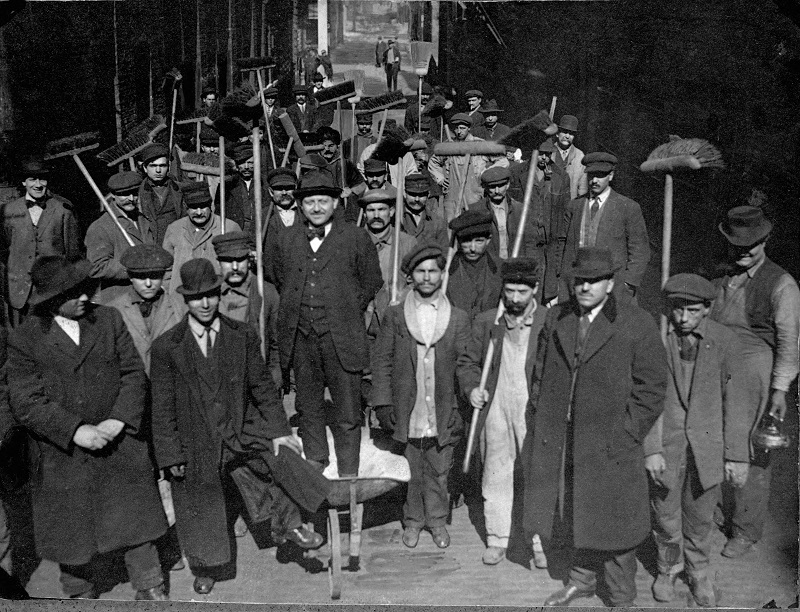

The economic misery was exacerbated by an extraordinarily harsh winter in 1893, Coxey’s army of unemployed marched to Washington, D.C. in 1894, and in April of 1894 more than 40,000 workers were reported to be involved in over thirty national strikes. The most dramatic and important of all of these strikes was the Pullman Strike which started in May of 1894 which tied up 50,000 miles of rail on July 26. Jane Addams, Florence Kelley and many others at Hull House spoke out and wrote about the circumstances and conditions of the strike. At one point 5,000 federal troops, called in by Grover Cleveland over the objection of Governor John Peter Altgeld, were camped alongside the Lake in downtown Chicago. [See full text of report on the Florence Kelley web site by using the path: About/Link to Other Web Sites/ Chicago/Pullman Strike Commission Report]

As with many former and subsequent financial crises, there were international roots and ramifications. The United States tariff policy played a role, as did the political stalemate over taxes, and whether United States currency should be backed by gold alone, or gold and silver. These issues remained central to the hotly contested presidential campaign of 1896 when the Democrat William Jennings Bryan was defeated.

As would be repeated a century later, the financial crisis was precipitated by an unexpected event, when Baring Brothers, a financial house in London, defaulted on 21 million English pounds of debt which had been collateralized by its heavy investment in Argentina. To cover the default the Bank of England borrowed from the Bank of France which borrowed from the Bank of Imperial Russia, and in November of 1890 there were numerous bank failures and run on currency in Europe.

The financial crash of 1893 would have come sooner to America had there not been a bumper crop of wheat in the face of European famine, and thus gold temporarily poured into the coffers of United States banks. Then there was a political revolution in Brazil, followed by a banking crisis in Australia. And the economic depression in France and Germany depressed the price of silver. This further increased the immigration to the United States, and to Chicago.

A man coming to work in Chicago in 1893 might have sought a night’s lodging:

“… According to the best authorities, the floating population is about 30,000 single men, who are living at this present moment in lodging houses. … Within a stone’s throw of one of Chicago’s best private hotels can be found one of these lodging houses. It is a small, one-storied frame structure. Its sleeping accommodation consists of the one hundred and fifty beds which occupy the ground floor and basement. Upon entering the front door one is almost overcome by the odor, which more resembles that of a long disused tomb than that of a human dwelling place…. Stepping to the desk the visitor asked the price of a night’s lodging, and after being told deposited a dime…. Following the direction pointed out, the investigator entered the sleeping room. For a few moments it was impossible to see anything in the place, the only light coming from a dirty lamp at the farther end of the room, which was about fifty by twenty-five feet in dimensions; while the darkness was made more apparent by the smoke from a dozen pipes of the men who were lying in the beds and smoking. The arrangement of the room was certainly unique in character. The beds consisted of a piece of canvas, which was fastened to the wall on one side, while on the other they were supported by upright wooden poles which ran from the floor to the ceiling. They were arranged in tiers, four deep, and the covering on each bed consisted simply of one thin blanket, which in several cases was reeking with vermin. In the center of the room was a large stove filled with blazing wood which only served to dispel any breath of air which might by inadvertence have entered the apartment. In this place one hundred and fifty men sleep…’

William Stead, If Christ Came to Chicago pp 161-162

For further reading, see, Charles Hoffman, The Depression of the Nineties, An Economic History, Greenwood Publishing (1970).

Next: The Haymarket