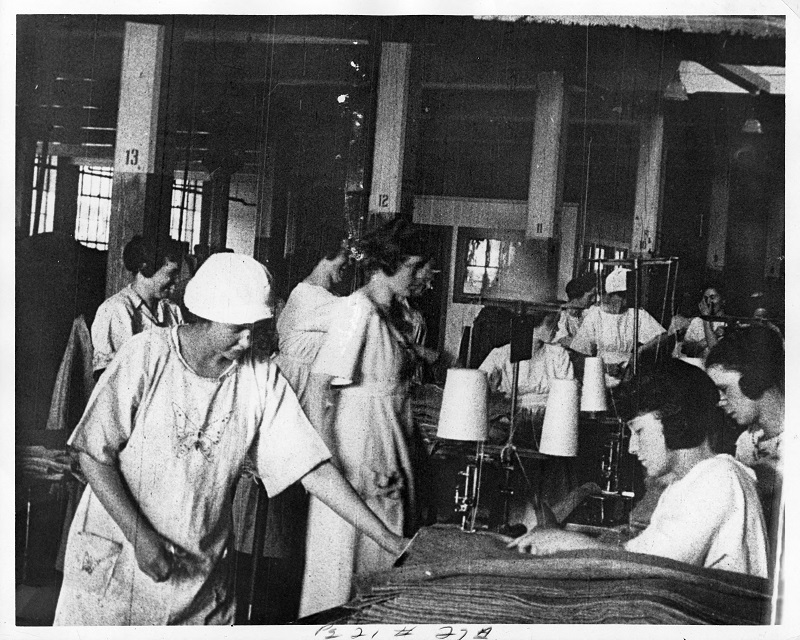

In May of 1894 Mrs. Florence Kelley, Chief of the State Board of Factory Inspectors, reported to the Chicago Health Commissioner several confirmed cases of smallpox within the tenements and sweatshops where she and her colleagues were working every day.

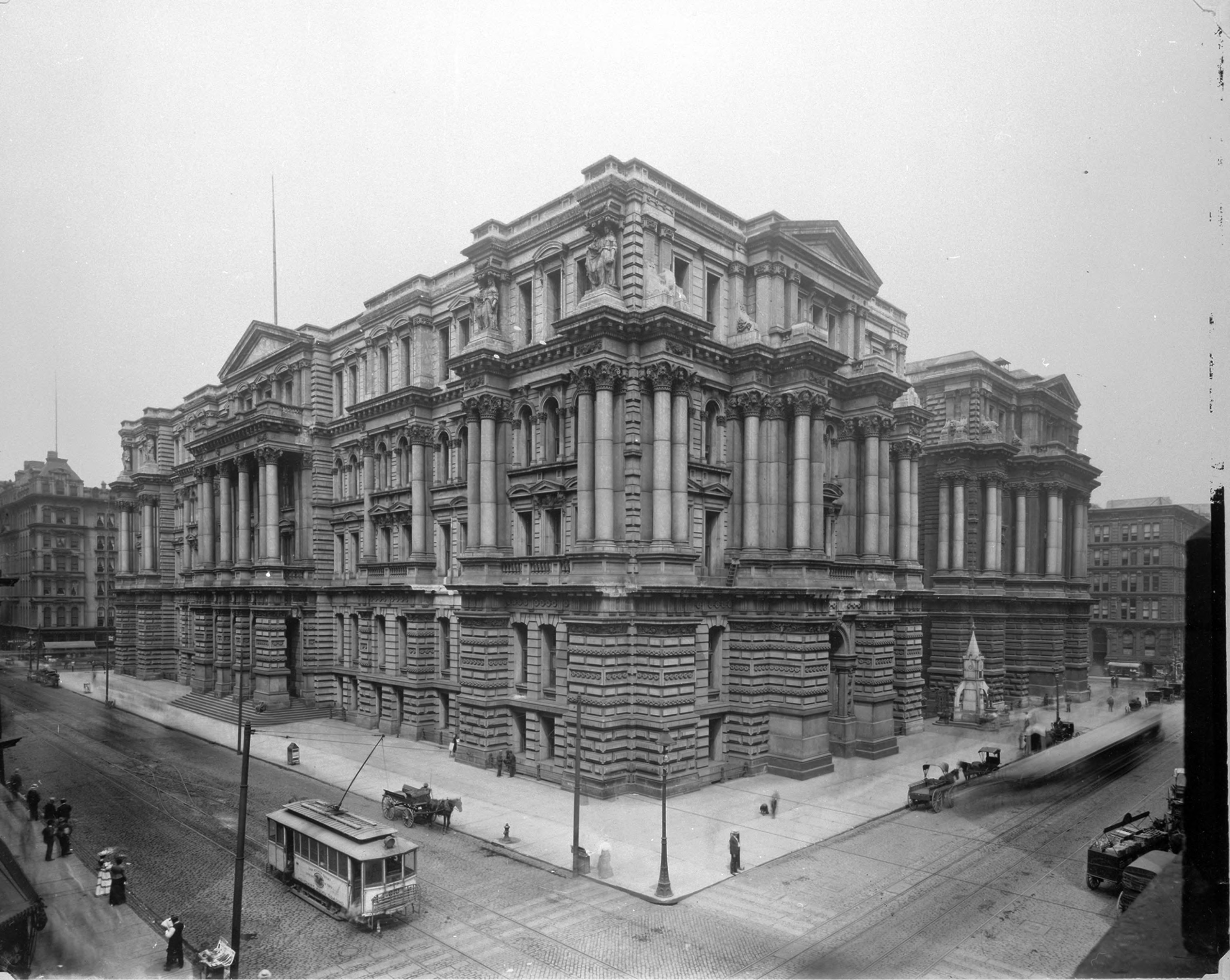

By May of 1894 the enforcement of the Factory Inspection Law was in full swing. The First Factory Inspection Report had been presented to Governor John Peter Altgeld on December 15, 1893,. Florence Kelley herself having been appointed July 7, 1893 and her associates a few days later. The Factory Inspectors were at work on July 15, 1893. There were at the height of the enforcement efforts a dozen factory inspectors, and over 66,000 factories to be inspected.The opponents to the law were also becoming organized, and the constitutional challenge to the law was being prepared and presented to the state courts under the masterful direction of Levy Mayer, who was on his way to becoming one of the most influential lawyers in Chicago.

“The Illinois Association of Manufacturers, establishing in 1893, seems not to have been in working order until after the new law took effect in July, or to have been too feeble to make any timely opposition. No sooner, however, had we begun to enforce the statute against violators in the tenement houses, by urging their employers to cut off supplies during the epidemic, warning them that goods found in the presence of infection would be summarily destroyed, than many workers showed us letters from the Manufacturers’ Association promising protection if they were molested by inspectors who were, the letters said, operating under a new law clearly unconstitutional…” [Florence Kelley autobiography p. 88]

Levy Mayer was born in Virginia in 1858, the child of 1855 emigrants from Bavaria, a place where at that time only Catholics were allowed to hold public worship or pursue trades and occupations. Levy Mayer’s unlikely biographer, Edgar Lee Masters – another lawyer, one who for a time shared space with John Peter Altgeld and Clarence Darrow, a writer whose Spoon River Anthology is familiar to generations of American high school students – notes that Levy Mayer, the champion of the Manufacturers’ Association, the man who crafted the legal strategy which brought the challenge to the statute to the Supreme Court of Illinois, was against direct election of senators, against the primary system for nominating public officials, and against the income tax. The cardinal principles of American democracy were, he believed, individual liberty and noninterference with business as guiding principles.

Levy Mayer himself was a better businessman than most of the heads of manufacturing firms whom he cobbled together to form the Illinois Manufacturers’ Association. Levy Mayer hated socialism and abhorred the dreams of populism. The law was or should be a business, that is, to make money and protect property, and the business of the law was to lay down and enforce reasonable rules for business, so that business could do its business under the protection of the rule of law. Business needed the law to make the system reliable, needed contracts which were respected and understood, needed to know that there would not be strikes or riots, and business did not need interference from reformers or people who thought it was their business to clean up the tenements. When one of many financial panics struck Chicago in 1893, he was the attorney for one of the largest financial institutions, the National Bank of Illinois.

Always precocious, like Florence Kelley, always the bright child, Levy Mayer enrolled in the Jewish Training School, where the some of the other students later had a connection to Hull House. Then at age 12 he went to Chicago High School, then located at the corner of Monroe Street near Halsted. He received grades of 84-90 in Latin and 82-96 in Greek, and 97-99 in Spelling, and as high as 97 in Rhetoric.

His deportment average was 99. A reminder of this praised deportment is seen in the serenity of his representation in his portrait by Leopold Seyffert of Chicago, which today stares back at you from the Entrance Lobby of Levy Mayer Hall, filling the block between Chicago Avenue and Superior Street, the building bearing his name which became the first autonomous home of the Northwestern School of Law.

Although the budget of the Factory Inspectors office, and Florence Kelley’s own salary, were both small, by the spring of 1894 momentum had been built by the convergence of several different projects, all emanating from Hull House and all centered on the working and living conditions in the tenements in the Nineteenth Ward, on the other side of Halsted Street.

Many years later, this is how Jane Addams remembered Halsted Street:

For six miles the street is lined with shops of butchers and grocers, with dingy and gorgeous saloons, and pretentious establishments for the sale of ready made clothing … Hull-House once stood in the suburbs, but the city has steadily grown up around it and the site now has corners on three or four foreign colonies…. Between Halsted Street and the rivers live about ten thousand Italians – Neopolitans, Sicilians,and Calabrians with an occasional Lombard or Venetian. To the south on Twelfth Street are many Germans, and the side streets are given over almost entirely to Polish and Russian Jews. Still farther south, these Jewish colonies merge into a huge Bohemian colony so vast that Chicago ranks as the third Bohemian city in the world. To the Northwest are many Canadian-French, clanish in spite of their long residence in America, and to the north are Irish and first generation Americans. On the streets directly west and farther north are well-to-do English-speaking families, many of whom own their houses and have lived in the neighborhood for years; one man is still living in his old farmhouse.” [ 20 years at Hull House, p. 98]

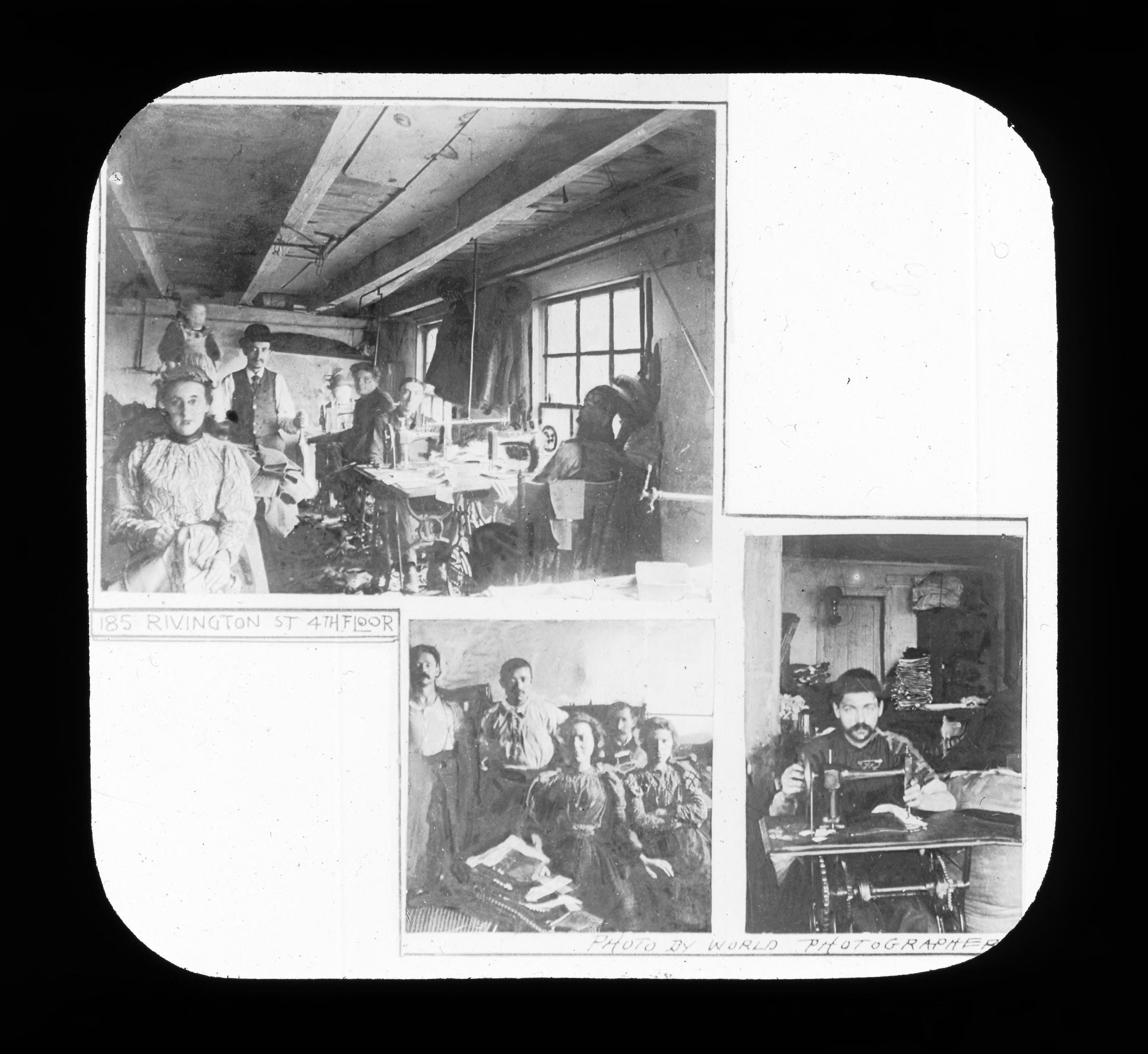

This ethnic diversity, as well as the precise economic conditions of the people living there, was captured by Florence Kelley and her associates in the maps and text of Hull House Maps and Papers. Published in 1895, the astonishingly detailed economic data published in this volume was conducted as part of the national study of the living and working conditions in The Slums of the Great Cities. This was the data collected by the four schedule men from Washington, D.C. who came to live at Hull House from April 6, 1893 to July 15, 1893. With the assistance of Hull House residents, they collected information from each tenement, household and factory within the area bounded by Halsted Street on the west, State on the east, Polk on the north and Twelfth Street on the south.

The schedules filled out by the four schedule men from the federal government were treasure troves of original information, and each night the day’s information was copied by Hull House residents. These data then formed the basis for the Hull House maps, and for the essays.

The poor districts of Chicago present features of peculiar interest, not only because in so young a city history is easily traced, but also because their permanence seems less inevitable in a rapidly changing and growing municipality than in a more immovable and tradition-bound civilization. Many conditions have been allowed to persist in the crowded quarters west of the river because it was thought the neighborhood would soon be filled with factories and railroad terminals, and any improvement on property would only be money thrown away. But it is seen that as factories are built people crowd more and more closely into the houses about them, and rear tenements fill up the few open spaces left. Although poor buildings bring in such high rents that there is no business profit in destroying them to build new ones, the character of many houses is such that they literally rot away and fall apart while occupied…. Where temporary shanties of one or two stories are replaced by substantial blocks of three of four, the gain in solidity is too often accompanied by a loss in air and light which makes the very permanence of the houses an evil. The advantages of indifferent plumbing over none at all, and of temporary cleanliness of new buildings over old, seem doubtful compensation for the increased crowding, the more stifling atmosphere, and the denser darkness in the later tenements. In such a transitional stage as the present, there is surely great reason to suppose that Chicago will take warning from the experience of older cities whose crowded quarters have become a menace to the public health and security.” [ Hull House Maps and Papers. Pp. 9-11]

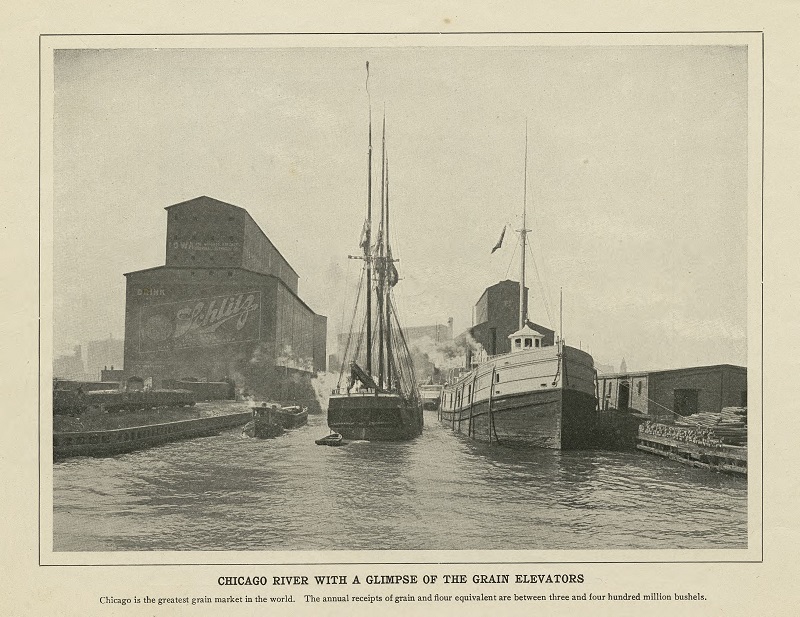

In July of 1893 when the Factory Inspection Law had first gone into effect Chicago was still in the middle of the euphoria of the Fair. The city and the country were not yet in the grip of the economic depression which deepened as winter approached. The World Columbian Exposition, which built the Great White City, closed in October of 1893. The Fair had kept the city and its millions of first time visitors in a state of continual bustle for months. Florence Kelley took her oldest son and said it was the most beautiful thing she had ever seen.

When the Fair was over, a fire burned many of the buildings in the White City which had been built as temporary structures with plaster and straw. Only the Museum of Science and Industry remains.

In a large sense, after the Fair closed and one of the coldest winters in Chicago history settled in, the party was over. The city which had prided itself and preened itself in the surprised admiration of the rest of the world now asked itself how much misery would be tolerated? More than 100,000 unemployed men were sleeping on the streets, in the police stations, and in city hall. Hull House became a shelter for homeless women. Without the city’s recent pride in the glorious Fair, perhaps questions about injustice would not have been asked with the such intensity and outrage.

In the winter of 1893 the city and the country were sinking into the worst economic collapse since the Civil War. The depression lasted until 1896. The railroads which had been moving hundreds of thousands of people and goods across the country to new jobs and new opportunities, fueling the economic and political expansion of the 1880’s were bankrupt, and beset by strikes.

The extravagances and excesses of the prior decade, were cast in a new light in comparison to the revelations brought forward by Florence Kelley and others of how people were living and working in the tenements and sweatshops. The privileged rich in Chicago were fiercely proud of their city and themselves often only a generation away from being recent immigrants.

The additive accumulation of information from the factory inspections, the research done for the U.S. Department of Labor, the social service work done by the police and many others, as well as the all too apparent destitution and visible evidence of misery from people on the street after recent economic failures, garnered the attention of the those who had resources and political authority.

People like Jane Addams, Henry Demarest Lloyd, Florence Kelley, William Stead spoke out. People listened. It was this momentum which had carried the Factory Inspection Law through the state legislature, and supported the early work of Florence Kelley and her associates. It was this momentum which resulted in the election of John Peter Altgeld as Governor of Illinois. The commitment of prominent Chicago families to the welfare of the city as a whole did not disappear when the Fair closed.

The smallpox epidemic began in January of 1894 and by May there were over 1400 cases known and more suspected but unreported. Florence Kelley presented a Special Report on July 1, 1894 to Governor John Peter Altgeld, titled ‘ Small-Pox in the Tenement House and Sweat-Shops of Chicago.’ The Factory Inspectors claimed authority to report smallpox cases under the factories and workshop law requiring that every workshop and factory be kept in a ‘cleanly’ state.

The argument that the Factory Inspection Law was justified because it was a protection of the public health was important to the defense of the constitutionality of the Factory Inspection Law, already under attack from Levy Mayer and the newly energized members of the Illinois Manufacturers Association.

The small pox epidemic understandably frightened the residents of Chicago, especially since the garments manufactured in the tenements were sold all over the city and shipped outside of the state. Florence Kelley and her inspectors paid particular attention to the cloak manufacturers. Smallpox, it was known, could be carried in garments and fabrics.

Florence Kelley and her associates argued the City Health officials were not doing their job of quarantining people, monitoring vaccinations, or in protecting the health of the uninfected or treating the sick. The rumor was that a case of small-pox at the Fair had been concealed, and thus the spread of the disease was unreported. Since the Factory Inspectors were in the tenements and sweatshops every day throughout the summer and fall of 1893 and 1894, they saw people sick and dying who did not appear in the official city reports.

“… we found so many cases of small-pox which had not been reported to us that we soon ceased to depend on the city hall lists alone, and supplemented them with the daily lists of diagnoses of the district physicians, of which the number varied, during a part of the time, from 30 to 47 in a single district in a day…” [Special Report, Small-pox p. 7]

Then, when the full blown epidemic occurred Florence Kelley and her fellow inspectors were in a position to report in detail the deficiencies of the work of the city health inspectors. For the Factory Inspectors and their political allies the small-pox epidemic was a tragic opportunity, to bring to public attention the conditions in the tenements and to establish their own roles as guardians of the public welfare. It was well known in 1894 that the small pox virus was air born and could be carried in cloth, in fact cloth and clothing were hospitable places for the virus. The value of vaccination was also understood.

Florence Kelley and her associates attempted unsuccessfully to have the City Health Commissioner, Doctor Arthur Reynolds, fired. Dr. Reynolds was to reassure the City Council and the readers of the newspapers that with a bit of fumigation, not documented where or when, every one would be safe. The documentation and record keeping of who went to the pest house, as the hospital for smallpox was called, and when they left or whether it was feet first, was abysmal. Florence Kelley sent a notice to the wholesalers and tailors saying that clothing found in homes where there was an infected person would be destroyed. And she held a public burning of some expensive cloaks about to be shipped out of state.

During the small-pox epidemic Florence Kelley did not visit her own children for several weeks, being fearful of infecting them. And during the visits of the Illinois state legislators, in preparation for the introduction of the Factory Inspection Law, one of the legislators would not enter the tenements, saying, that he had young children at home and feared for their health.

The center of the epidemic was the section of the slums which had been the subject of investigation by the United States Bureau of Labor. It was the area mapped in Hull House Maps and Papers, an area very familiar to Florence Kelley and the residents of Hull House.

The health of the children in the tenements and sweatshops was abysmal for many reasons: poor sanitation, open toilets, uncollected garbage full of rats, insects and other vermin, cholera, dysentery, typhoid, tuberculosis, malaria, intramural burials, overcrowded living conditions without the ability to wash the body or clothes, lack of fresh running water, contaminated food and lack of adequate nutrition, living and working conditions in dilapidated buildings surrounded by dangerous machinery, parental neglect and carelessness, the hazards caused by horse drawn vehicles and later street cars, violence in the home and outside it, and many many other aspects of everyday life faced by these children every day.

It was not surprising or unreasonable that Florence Kelley and her inspectors were obsessed with fresh air, ventilation, the removal of garbage and human waste, and access to fresh, clean water. Only forty per cent of the children in the Nineteenth Ward lived to the age of five. Yet, amazingly, the overall mortality rate of the city declined during this period.

With a justified suspicion people avoided the mandatory quarantine notice. When the factory inspectors found a child or an adult sick or dying of smallpox in a tenement, often when they returned the next day with the order to enter the small pox hospital, the infected family would be gone without a trace.

Chicago’s reputation for being an unhealthy place was a source of defensiveness, and one of the triumphs of the Fair was that 27 million people came and were surprised by the beauty and cleanliness of the city. The crowded housing for the tens of thousands who poured into the city in even greater numbers as the economic crisis of 1893 deepened aggravated many health problems in the tenements.

The single occupancy rooms housed as many as a thousand men in a single building, with one window at the end of a long corridor, with tiered sleeping quarters separated by wired grates. What fresh air existed was sucked out by the single coal stove lit to keep out the cold. Regulation of such places, and of the more than seventy slaughterhouses was relatively recent.

The germ theory of disease was not wholly accepted, and surgery in unsterile conditions, as well as practices such as bleeding, emetics, the administration of large quantities of mercury and opium for sickness often aggravated the situation. Infected teeth and gums were exacerbated by medications such as calomel which caused loss of teeth. The market for patent medicines, alcohol, and cocaine, all of which were unregulated, flourished. In New York, the attempt of Lazare Wischnewetzky to import the Zander technology was another example of this trade in products promising better health.

Florence Kelley, Jane Addams, Henry Demarest Lloyd and their colleagues were much influenced by the people and writings and the conditions they witnessed in Europe, especially London. The maps in Hull House Maps and Papers were modeled upon a similar effort in London.

next: Springfield Illinois, March 1895