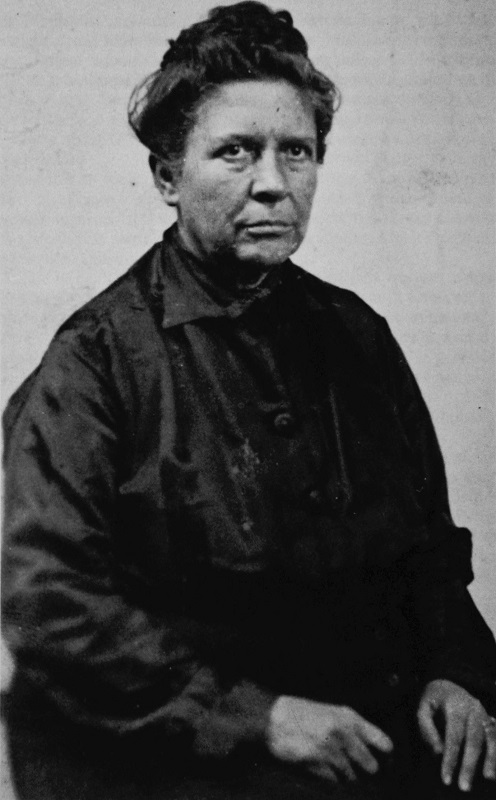

Florence Kelley rented rooms in the early weeks of 1895 at The Leland Hotel in Springfield, in order to work on her Third Annual Report under the Factory Inspection Law and to wait for the Illinois Supreme Court decision in Ritchie v. People, the case brought by Levy Mayer and the Illinois Manufacturer’s Association challenging the constitutionality of the 1893 Factory Inspection Law.

The weather in Springfield on March 16, two days after the Ritchie decision was handed down, was reported as temperature in the low 20’s, with north west winds, cloudy with traces of precipitation. A grey, dreary and damp spring day in Springfield when the opinion, also a disappointment, was handed down by the Supreme Court of Illinois.>

The enforcement of the factory inspection law took place throughout the state, and the Third Annual Report contained a special section on child labor and on employment of children in the glass manufacturing industry, especially with the Illinois Glass Works Company at Alton, Illinois.

The glass works industry was one of the largest employers of children and their practices among the most exploitative. Working children were shipped down the river from orphanages in East St. Louis and elsewhere to perform dangerous tasks in an exceptionally inhuman environment, work which the adult men in the factory refused to do and refused to allow their own children to do. For Florence Kelley, the plight of the children in the Illinois glass factories in the 1890’s was reminiscent of conditions she had seen years earlier in factories employing children in Pennsylvania, and later in Britain. The Glass Works Company in Alton was defiant in its refusal to provide information on the number of boys under fourteen employed.

“The failure to file affidavits, keep a register, post notices, and correct wall records, shows the defiant dispositions of the Glass Company…. At the time of our inspection of Monday last, President Smith refused absolutely to comply with any of the provisions of the law, and intimated that, if compelled to do so, and to discharge the children hitherto illegally employed under 14 years of age, the company would close its furnaces, discharge its employees, and turn them over to the soup-house for support..

On Monday, President Smith alleged that there were no unemployed boys in Alton. Yesterday, when large numbers of well-grown boys were sliding and skating on the Mississippi, he modified his statement, saying ‘No boys unemployed who are willing to work for $2.70 a week.'…

The earnings of the blowers depend somewhat upon the speed of the boys who fetch and carry. The lads are therefore kept running at their highest rate of speed. It was impossible to get a coherent statement of name, age, address, etc. from any boy in the works. One would say, ‘My name is Faber,’ then run with his load of bottles and come back and say, ‘I live in a boat down by the river,’ then run for another load, and come back and say, ‘I am going to be 8 next summer,’ and so on. Among the twenty-four lads whom we questioned, not one ventured to pause long enough to put together any two of the above statements. The little runner’s eye was invariably fixed, during these momentary pauses, on the blower for whom he worked.

Young children, with heads and hands bandaged, where they have received burns from melting glass or red-hot swinging rods, dodging in all directions to escape the danger which each causes the other where their paths cross, while the blowers’ long pipes swing over their heads, are not doing ‘light and easy work.’…

While this conspicuous danger strikes the eye at once, the greater and more permanent injury to all the young children may be overlooked in a casual visit. The speed required and the heated atmosphere surrounding the fires, render the boys’ continuous running most exhausting. An hour’s steady trotting in the open air tires a healthy school-boy of 7 to 14 years; but these little lads trot hour after hour, day after day, month after month, in the heat and dust.

The strain must be borne by night as well as by day, for there is no legal limit to the hours which may be required of the boys, nor any restriction upon night work for them. Nor is there any discrimination in favor of employing the older boys at night. Children 7 & 8 years old work until 3 a.m., and then scantily clad, go from their exhausting running in the hot air beside furnaces out over the ice, through the chill air on the early morning, to the tents and boats beside the frozen river…. In all of the families we visited none of the children have ever gone to school.

When the river is frozen, the people living in tents and boats have no water except ice melted over drift-wood fires. They are therefore unspeakably filthy, and the home habits of the children are strengthened in the grime of the furnaces.

The children are an unusually wretched-looking set. They are ill-fed, ill clothed, profane, obscene, and in many cases unable to work without stimulants. Boys of 7 to 10 years old chew tobacco habitually, and boys 10 to 14 are in some cases habitual drinkers of the beer and whisky which are freely sold just across the street from the works. …

The mayor of Alton, M. J.J. Brenhold, acted as counsel for the glass company throughout my stay in Alton. He has also appointed to the school board Mr. Levis, an active member of the glass company.

The school board has never enforced the school attendance law. It has appointed no truant officer. The Humboldt school, which is nearest the glass works, is overcrowded, During the present session there have been 240 applications for admission to the Alton schools refused for want of accommodations…” [Third Annual Report of the Factory Inspectors. P. 15-17]

During this time Florence Kelley was taking night courses at the Northwestern University School of Law.

In the portrait of Levy Mayer, unveiled at the building dedication in 1926, he is seated, ensconced in his profession, sartorial, scholarly, staring back with the confidence of the well tailored and successful representative of the Law, his own death in 1922 unexpected, leaving his widow, Rachel Meyer, to endow and have named after him the first independent free standing building to house the Northwestern University School of Law. The School of Law then became housed at the Lake Shore campus, purchased by the University in 1920,a campus that would eventually include dormitories, classrooms, the School of Medicine, a branch of the School of Business, the School of Dentistry, and a School of Nursing.

Florence Kelley would graduate from Northwestern University School of Law in June of 1895 and be admitted to the bar June 12, 1895. She was not required to “article,” the requirement for recently graduated law students to work (at a very low salary) for a practicing lawyer in order to gain experience before being allowed to offer their professional services.

While at Springfield waiting for the opinion of the Illinois Supreme Court Florence Kelley wrote to Professor John Henry Wigmore asking if she could postpone to the taking of her law school examination because business detained her in Springfield. The study of law consisted at that time of attending lectures and taking examinations. Florence Kelley was not the only woman in her class. Being the Factory Inspector, a full time job, and her being in Springfield did not delay her graduation in June of 1895.

On March 14, 1895 the Supreme Court of Illinois ruled that the eight hour provision for women in the Factory Inspection statute was unconstitutional. They did not hold the entire statute unconstitutional. The prohibition against the employment of children under 14 remained, as did the powers of the inspectors. The opinion was, however, written broadly as a limitation on the authority of the state legislature.

Florence Kelley notes in the Third Annual Report:

“In annulling this section, the ground taken by the court, namely that regulation of the hours of labor is in excess of the powers of the legislature, is of curious interest in contrast with the established policy of those States and countries where this power to regulate is no longer in question, where the principle is accepted and acted upon, that the care of the health of the factory employee is a legitimate subject for special legislation…

It remained for the Supreme Court of Illinois to discover that the amendment to the Constitution of the United States passed to guarantee the negro from oppression , has become an insuperable obstacle to the protection of women and children. Nor is it reasonable to suppose that this unique interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment will be permanently maintained, even in Illinois…”

The Supreme Court of Illinois had at that time a long history. It held its first session on January 12, 1801, while the state was still part of the Northwest territory. Shortly thereafter an act was passed requiring this court to deliver its opinions in writing. The court had concurrent original jurisdiction in ‘all cases, matters, and things pertaining to property, real, personal, and mixed, and exclusive jurisdiction of higher crimes and all cases in equity where the amount involved was in excess of one hundred dollars. It also had appellate jurisdiction in all cases, and other special powers. Judges were appointed to the court of the Illinois Territory, and commissioned by the Governor of the Territory.

The Illinois Constitution of 1818 created a Supreme Court with appellate jurisdiction only, initially consisting of a Chief Justice and three Associates. They were appointed by the two branches of the General Assembly and commissioned by the Governor of Illinois. The State was divided into four judicial circuits and justices were required to ride circuit throughout the state, a common requirement. Subsequently additional circuits were created.

Under the constitution of 1870, the court consisted of seven judges, each of whom were elected by the people of the seven districts for a period of nine years. Each year the court would elect a Chief Justice. The court sat primarily in Springfield, with sessions periodically held at Vandalia and Kaskaskia. The requirement that the Supreme court travel was not abolished until 1897.

The Justices sitting on the Supreme Court of Illinois when Ritchie v. People was decided were: Jacob Wilkin, Chief Justice; Alfred M. Craig; Benjamin D. Magrudger, the author of the opinion; Joseph V. Bailey; David J. Baker; Jesse J. Phillips; and Joseph N. Carter. Benjamin D. Magruder also was the author of the opinion in the Haymarket case, upholding the capital sentences for conspiracy to commit murder. [Read more: Haymarket Affair- and its Related Documents; The First Mayday: the Haymarket speeches (1980); Anarchy and Anarchists (1889)]

Like most of their generation these Justices all had direct experience of the Civil War, several of them, like John Peter Altgeld, having served as soldiers in the War. The Haymarket case and the subsequent events, as well as the identification of the Haymarket defendants with the eight hour movement, would have been recent memories for these Justices, as would the occupation of Chicago by federal troops in 1894 during the Pullman episode and other strikes and labor actions.

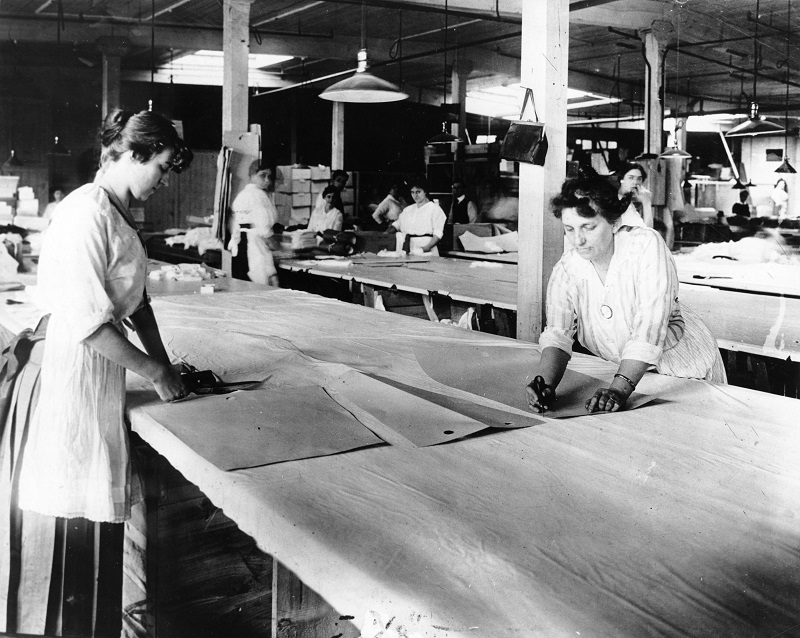

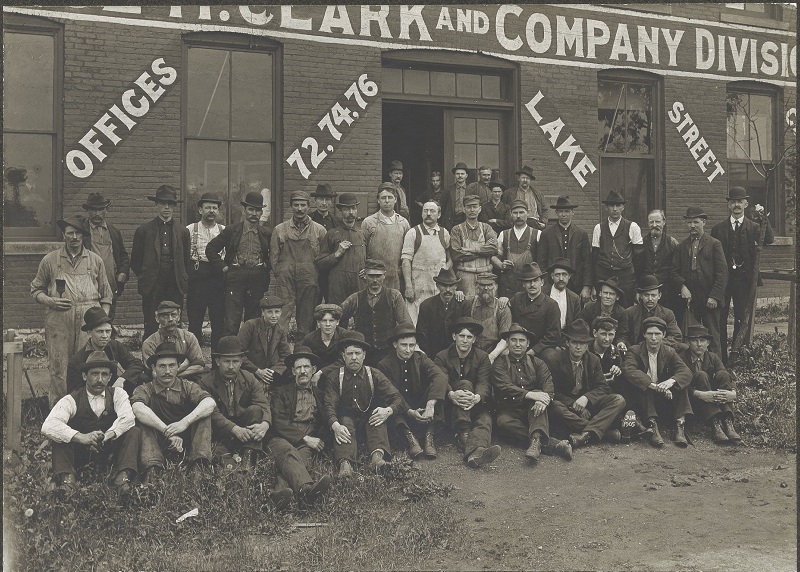

The eight hour day was the symbol and the rallying cry, the red flag – literally and figuratively – and including an eight hour provision for women in Illinois in the Factory Inspection Law was a throwing down of the gauntlet. The strike of 1886, just before the Haymarket bomb, called out several hundred thousand marchers in Chicago, and was linked to the panic and caste hatred which crystallized around the Haymarket trial and executions. After Haymarket many manufacturers in Chicago and elsewhere refused to negotiate with labor unions, and bitterness and disillusionment characterized both sides. For those representing labor, the eight hour day was honest pay for honest work; for the manufacturers it was ten hours pay for eight hours work, and there was always the option to have people work 14 hours or more.

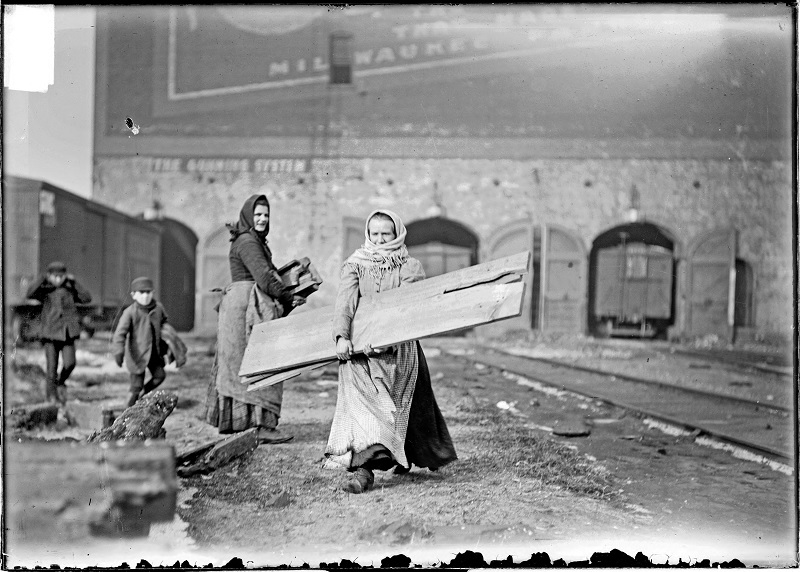

Chicago’s throbbing preeminence as the building, manufacturing and shipping center of the country was ribbed in steel by the railroad lines meeting on State Street and leading to the river and the stockyards, where their wide eyed, squalling, bleating, and somber cargoes were unloaded into the waiting slaughterhouses. Much of the most valuable cargo was two legged. The campaign for the eight hour day was begun in 1879 by the Chicago Typographical Union, and later managed by the Socialist Labor Party, the Party which Florence Kelley staunchly resisted joining in Chicago, although that would be the political party closest to her ideological sympathies. In the late 1880’s, Florence Kelley was in New York City watching the same political forces combine, reel in and unwind, and then regroup in the context of the 1886 New York city and national elections. In Chicago the eight hour movement had the support of many small and large unions, but dissension was brought by powerful groups such as the Packers Association. The strength of Marxist socialism within the ranks of labor was seen as a fundamental challenge to the private ownership of property and the autonomy and financial power of large capitalist enterprises, such as the railroads, the meat packing industry, the reapers, and the lumber owners. The big business interests were right, organized labor did want to confront capitalist ownership at its core. And the union organizers were not wrong: the manufacturers would do anything, legal or illegal, lockouts, hiring thugs to beat up organizers, to stop labor from being unified.

The American Federation of Labor convention in Chicago in 1893 brought more than 100,000 people to the city, called for legislation establishing the eight hour day, factory inspection, employers’ liability for worker injuries, and the abolition of sweatshops. [Read more]

For Florence Kelley after the opinion in Ritchie, the issue was how to continue to fight another day:

“The situation is far from hopeless. Even under the decision as it stands, further legislative projection for minors is not impossible…” [Annual Report of the Factory Inspectors of Illinois, 1895, p. 7]

The Fourth Annual Factory Inspectors Report, filed December 15, 1896 continued the investigations into the working conditions of children in the stock-yards, the glass works, the sweat-shops, other unregulated industries and linked the enforcement provisions of the Factory Inspection Law to the provisions of the Compulsory Attendance Law passed in 1893. [Annual Report of the Factory Inspectors of Illinois, 1895, pp. 15-31]

Both the Third and Fourth Annual Report supplied a wealth of specific details and statistics as well as the summary of prosecutions and convictions under the statute. The Third and Fourth Annual Reports recommended additional legislation.

next: The John Crerar Library