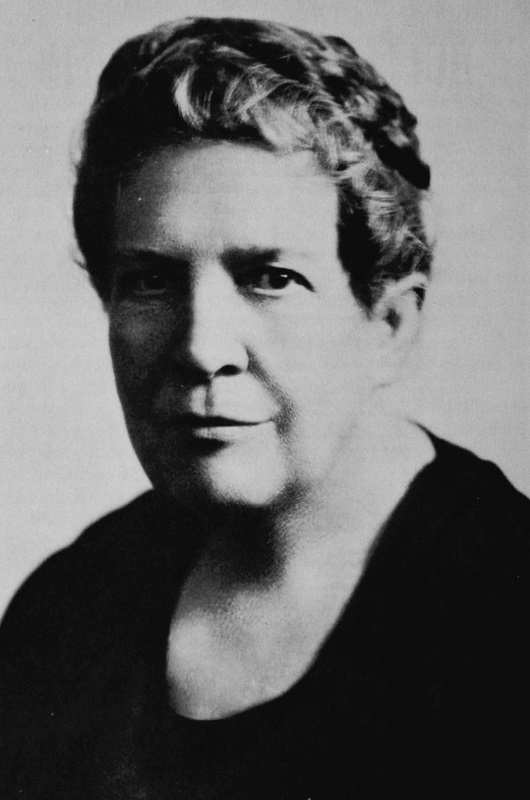

In December of 1897, Florence Kelley found herself working as a part time librarian for the John Crerar Library, a special reference collection established by the estate of John Crerar, after being unexpectedly fired as Chief Factory Inspector in August of 1897.

John Peter Altgeld was not reelected Governor of Illinois in the fall of 1896 during a Republican sweep of national and state elections where the stability of currency was a principal issue. Major William McKinley, a modest civil war hero and congressman, was elected President over Illinois native son William Jennings Bryan. One commentator noted: “McKinley had the gift, invaluable to a politician of narrow vision and limited understanding, of emitting sonorous platitudes as though they were recently discovered truths.”

The continuing depression of 1893, the Pullman strike, the presence of federal troops in Chicago against Altgeld’s wishes, and Altgeld’s pardoning of the remaining Haymarket defendants all contributed to his defeat.

As for the national scene, in 1895 Henry Adams wrote to his brother, describing the President and his Attorney General, the force behind the occupation of Chicago by federal troops, using the following language: “Cleveland and Olney had relapsed into their normal hog-like attitudes of indifference, and Congress is disorganized, stupid and childlike as ever. Once more we are under the whip of the bankers.”

During this election Florence Kelley, Jane Addams and their colleagues were unsuccessful in unseating Johnny Powers, the Alderman from the Nineteenth Ward, known as one of the leaders of the boddlers, as corrupt city officials were called.

Initially the newly elected Governor John R. Tanner promised Florence Kelley that he would not fire her as Chief Factory Inspector, while at the same time he was already negotiating her replacement from amongst the ranks of her adversaries. Governor Tanner selected as Chief Factory Inspector Louis Arrington, a man who had worked for 27 years for the Illinois Glass Works at Alton, the most obdurate of manufacturers opposing factory inspections. Arrington had actually been convicted of violating the act he was now charged with enforcing. Later, Florence Kelley wrote: ‘Throughout his term of office, there were no prosecutions for violations of law by glass manufacturers.’

To support herself, Florence Kelley again turned to public speaking, writing, translating, and editing. The job at the John Crerar library was a stop gap until her appointment as Secretary to the National Consumers’ League in New York, a job which began May 1, 1899, and required her to move to New York.

At this point Florence Kelley obtained an official divorce from Lazare Wischnewetzky, appearing before the same Judge Frank Baker who heard the habeas corpus a few months after her arrival in Chicago. The grounds for divorce were those set out in the hearing in 1892. Lazare Wischnewetzky did not appear to contest the proceeding. The divorce resulted in Florence Kelley being awarded permanent custody of her three children, and also the right to use the name of Florence Kelley, as she had been known in Chicago since 1892.

The battle over the hours legislation was not over, however. While Secretary of the National Consumers’ League, Florence Kelley and her associate, Josephine Goldmark, persuaded Louis Brandeis, to argue before the United States Supreme Court in defense of an Oregon law limiting to ten the hours women could work in a laundry.

On November 14, 1907, Florence Kelley and I were actors in a little scene which, though of course we did not realize it then, marked a turning point in American social and legal history. We had come to Boston to see my brother-in-law, Louis D. Brandeis, then a practicing attorney in Boston, and we sat in the back library of his home on a little street called Otis Place, overlooking the widening of the Charles River in Back Bay. We had come to ask Mr. Brandeis to appear in the Supreme Court of the United States to defend the Oregon ten-hour law for women, attacked as unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment. The case – soon to become famous – was Muller v. Oregon.

Mr. Brandeis looked out over the river. “Yes,” he said, thoughtfully, “I will take part in the defense.” Thus began that collaboration between Mr. Brandeis and the Consumers League which gave a revolutionary new direction to judicial thinking, indeed to the judicial process itself. Mrs. Kelley who had seen her work in Illinois in protecting women from excessive hours of labor destroyed by an adverse court decision, whose attempt to mitigate the evils of industrial homework was frustrated by a similar decision in New York, had now found a champion to fight her battles in the courts with, as it proved, magnificent success.

Back of that quiet scene in the Brandeis library lay a long chain of events in courts throughout the land.

Louis Brandeis not only was familiar with Florence Kelley and her work, but he knew and admired Henry Demarest Lloyd and had himself visited in Chicago and was a participant in the American Institute which founded in 1910 the scholarly publication on criminal law, later to be known as Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, which continues to be published at the Northwestern University School of Law.

Louis Brandeis agreed to represent the National Consumers League for no fee:

Mr. Brandeis listened to Mrs. Kelley’s story and agreed to act as unpaid counsel for the National Consumers League in defense of the Oregon ten-hour law for women. He made only one stipulation: he would present a brief and take part in the oral argument only if invited to represent the state of Oregon by the state’s attorney in charge of the defense.

He then outlined what he would need for a brief: namely, facts, published by anyone with expert knowledge of industry in its relation to women’s hours of labor, such as factory inspectors, physicians, trades unions, economists, social workers. If I could return to Boston within a fortnight with such printed matter, sufficiently authoritative to pass muster, we would then work up the material in the form of a brief.

Mrs. Kelley and I returned to New York with our work cut out for us. A fortnight to amass the necessary documentation – without personnel, money, or anything but a general idea of the foreign literature on the subject and a complete skepticism as to the existence of any comparable material in American publications.

In these days of abundant tools of research, the paucity of our means seems almost laughable.

The result was the United States Supreme Court opinion in Muller v. Oregon, handed down on February 24, 1909, the establishment of a tradition which came to be known and the Brandeis Brief. After the Oregon decision Illinois and a number of other states enacted a new ten hour law for women in factories.

After Muller v. Oregon was handed down by the United States Supreme court, the Women’s Trade Union League of Chicago, representatives of more than a dozen trades and other allies proposed a bill providing that no women should be employed for more than forty eight hours in any one week on six consecutive days. Harold Ickes was the attorney for the League. The Illinois Manufacturers Association used the same arguments used in Ritchie in 1893, and the debate before the legislature was vigorous. The Illinois Manufacturers Association argued for a return to the eight hour provision because they were convicted it could not pass. The compromise was a law which limited women’s hours to 10 within 24. An injunction against the law’s enforcement was granted by Judge Tuthill on September 12, 1909. The injunction ignored the recent United States Supreme Court case and relied upon the cases in the 1893 Ritchie opinion.

The legal challenge to the 1909 statute was brought by the same box manufacturer who was the named plaintiff in the case outlawing the eight hour law in the Illinois legislation in 1895. Louis Brandeis’s brief in Ritchie II once again contained only a few pages of legal argument, and a long compendium of facts.

To present the oral argument Mr. Brandeis made an arduous journey in bitter mid-winter from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois. He considered this effort to secure a reversal of the old Richie decision so essential that he obtained a three-day adjournment of the U.S. Senate’s Ballinger investigation, in which he was then immersed.

In April, 1910 the Supreme Court of Illinois upheld the Illinois ten hour law. Levy Mayer did not argue the case himself before the Supreme Court of Illinois.

next: William Darrah “Pig Iron” Kelley